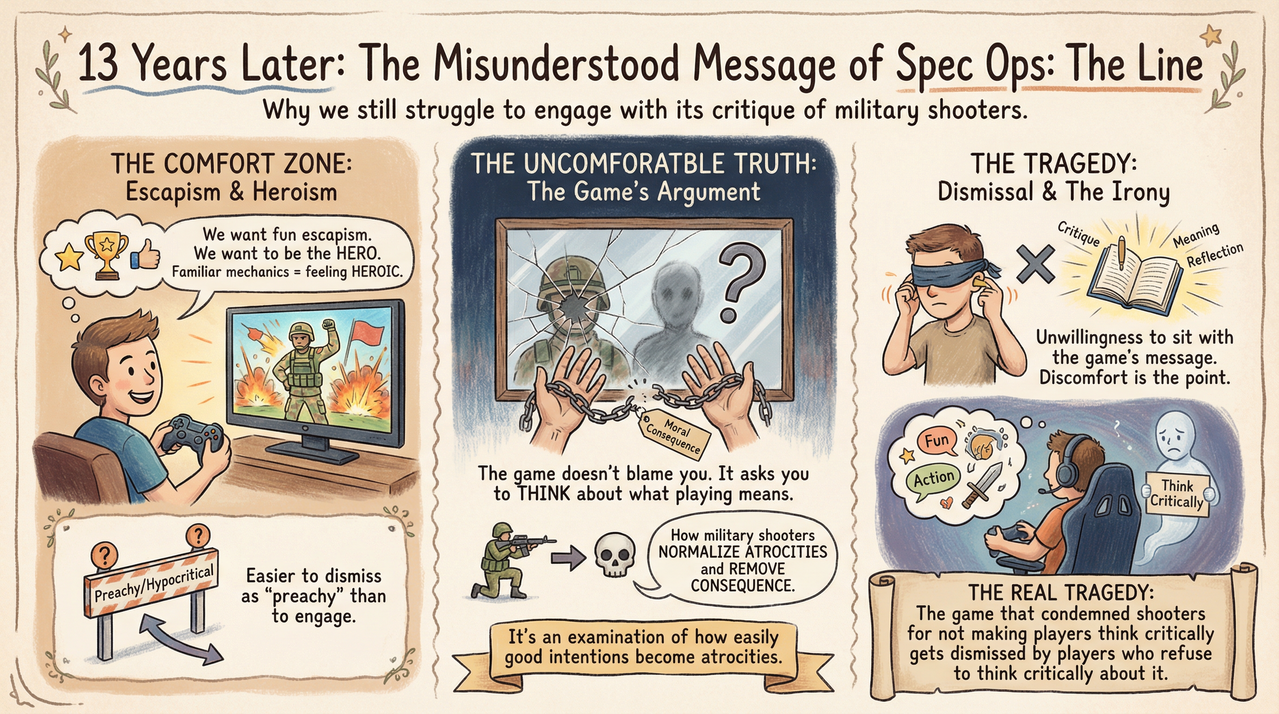

Spec Ops: The Line launched in 2012 as a seemingly generic military shooter set in a sand-buried Dubai. Thirteen years later, it’s considered one of the most narratively ambitious games ever made, a scathing critique of military shooters and American exceptionalism disguised as the very thing it condemns. Yet despite countless video essays, Reddit threads, and critical analyses, people still fundamentally misunderstand what the game is trying to say. The most persistent misconception? That Spec Ops blames you for playing it and suggests the only winning move is not to play at all.

The Game That Condemned You

Spec Ops: The Line follows Captain Martin Walker and his Delta Force squad as they enter Dubai after catastrophic sandstorms have buried the city. Their mission is simple reconnaissance, locate survivors and radio for help. What follows is a descent into madness as Walker disobeys orders, makes increasingly horrific decisions, and transforms from hero to war criminal while convincing himself he’s doing the right thing.

The game’s defining moment comes roughly halfway through when Walker uses white phosphorus, a chemical weapon that burns victims from the outside in and then inside out, to clear an enemy checkpoint. You control the targeting camera from above, watching through black and white thermal imaging as you rain down death on what appear to be enemy soldiers. After the attack, you walk through the aftermath, seeing charred corpses frozen in their final moments of agony. Then you discover the enemy camp contained hundreds of civilian refugees you just incinerated.

The Choice That Wasn’t

| What Players Think | What The Game Actually Says |

|---|---|

| The game blames you for playing | The game critiques how shooters remove moral weight from violence |

| Not playing is the only moral choice | Not playing misses the entire experience and message |

| Walker had no choice | Walker constantly chose to continue when he could have stopped |

| The white phosphorus scene is unavoidable | Walker could have turned back at any point before using it |

The biggest misunderstanding stems from loading screen messages that taunt players with lines like “Do you feel like a hero yet?” and “This is all your fault.” Many interpreted these as the developers literally blaming players for engaging with the game they created. This spawned the myth that lead writer Walt Williams suggested the only moral choice was to stop playing, to put down the controller and walk away before committing atrocities.

Williams has repeatedly clarified this was never the intent. In interviews, he explained that when playtesters expressed discomfort continuing after certain scenes, the team knew they’d struck the right emotional tone, not that players should literally quit. The loading screen messages aren’t accusations against you personally, they’re voiced by Walker’s fractured psyche as he struggles to rationalize his actions. The game isn’t saying “You’re a bad person for playing this.” It’s saying “Look at how video games normalize horrific violence by removing consequence and moral weight from your actions.”

The Myth of Player Choice

Another persistent misunderstanding involves player agency. Many critics argue that Spec Ops has no right to criticize players for their actions when the game is completely linear with no ability to make different choices. You can’t avoid using white phosphorus. You can’t refuse to keep pushing forward. The game forces you down a path then punishes you for taking it, which feels unfair and manipulative.

This criticism fundamentally misses what Spec Ops critiques. The game isn’t about your choices as a player, it’s about Walker’s choices as a character. You, the player, have one real choice: whether to keep playing or stop. Walker, the character, has dozens of choices throughout the story and consistently chooses wrong. He could have radioed for extraction after the first firefight instead of pushing deeper into Dubai. He could have obeyed orders to leave once he confirmed survivors existed. He could have retreated after discovering the 33rd soldiers weren’t hostile. He chose not to because he wanted to be the hero.

The game’s brilliance lies in making you complicit in Walker’s delusions by framing his increasingly unhinged decisions as standard video game objectives. Rescue missions, defend sequences, boss fights, these familiar gameplay structures make Walker’s descent feel normal because that’s what shooters train players to expect. You’re not being blamed for following the game’s linear path, you’re being shown how shooters use linearity to remove moral responsibility from violence.

What The Game Actually Criticizes

Spec Ops: The Line doesn’t criticize players. It criticizes military shooters that glorify war, American military intervention narratives, and the psychological impact of combat. The game is a love letter to Heart of Darkness and Apocalypse Now transplanted into the video game medium, exploring how people rationalize atrocities when they believe they’re acting heroically.

Walker represents the American military industrial complex and interventionist foreign policy. He arrives in Dubai believing he’s on a rescue mission, convinced the 33rd soldiers are either hostile or misguided and that only he can fix the situation. Every time evidence emerges that he’s making things worse, Walker doubles down, creating new enemies to justify continued presence. Sound familiar? The game isn’t subtle about its criticism of America’s pattern of entering foreign conflicts with good intentions that spiral into disaster.

More importantly, the game criticizes how military shooters present war as entertainment. Games like Call of Duty and Medal of Honor let players commit acts that would be war crimes in reality without any moral weight or consequence. You drone strike buildings, use chemical weapons, torture prisoners, and massacre hundreds of people, then receive achievement notifications and XP rewards. Spec Ops forces players to actually see the aftermath of those actions, to walk through the results of your violence and confront what you’ve done.

The Endings Nobody Understands

Spec Ops has multiple endings depending on player choices in the final confrontation. In all versions, Walker discovers that Colonel John Konrad, the 33rd’s commander and Walker’s personal hero, died weeks before Walker arrived in Dubai. Every interaction with Konrad throughout the game was a hallucination. Walker’s fractured mind created Konrad as a scapegoat to avoid accepting responsibility for his actions. The white phosphorus attack, the escalating violence, the civilian deaths, those were all Walker’s choices, not Konrad forcing his hand.

Players can choose to have Walker shoot himself, shoot the Konrad hallucination, or attempt to fight the rescue team sent to extract him. Each ending offers a different interpretation of Walker’s mental state and whether he accepts responsibility. The most haunting ending has Walker survive, get rescued, and radio that he’s coming home. When asked how he survived, Walker responds in Konrad’s voice “Who said I did?” suggesting Walker’s psyche is completely shattered and he now fully inhabits the Konrad persona.

These endings aren’t about punishing or rewarding the player. They’re about showing the psychological toll of modern warfare and how soldiers rationalize trauma. Walker can’t accept that he’s responsible for atrocities, so his mind creates elaborate justifications. The hallucinations, the villain he’s chasing, the orders he’s following, they’re all defense mechanisms to protect his ego from reality.

Why The Gameplay Had To Be Generic

One common criticism of Spec Ops is that the actual gameplay is mediocre. The cover-based shooting mechanics feel borrowed from Gears of War, the level design is linear, the AI is inconsistent, and the controls can be clunky. Critics argue that if the game wanted to critique military shooters, it should have innovated mechanically instead of just adding a dark story to generic gameplay.

This completely misses the point. The gameplay had to be generic because that’s what Spec Ops critiques. If the game introduced revolutionary mechanics or wildly different gameplay, it couldn’t function as commentary on standard military shooters. By making the gameplay familiar and conventional, the game lures players into the comfort zone of established shooter mechanics, then gradually subverts expectations through narrative and context.

The clunky controls and frustrating cover system aren’t bugs, they’re features. They create the stress and confusion of actual combat situations where perfect precision isn’t possible. The checkpoint placement that forces you to replay difficult sections and rewatch unskippable sequences makes the violence repetitive and exhausting rather than exciting. The game deliberately makes itself less fun as it progresses, reflecting Walker’s deteriorating mental state and the reality that war isn’t entertaining.

The Civilians You Keep Missing

Throughout Spec Ops, environmental storytelling reveals the civilian cost of the conflict between the 33rd, the CIA, and eventually Walker’s Delta Force. You pass bodies, encounter refugees, and witness the humanitarian crisis Walker’s actions exacerbate. Many players focus entirely on combat and miss these details, which is precisely the problem the game highlights.

In military shooters, civilians are typically invisible or exist only as set dressing. They’re objectives to rescue or collateral damage to avoid, but rarely people with agency or stories. Spec Ops makes civilians central to the narrative, the forgotten victims of violence between armed factions all claiming to act in their best interests. The white phosphorus scene works because it forces players to see the civilians they killed, to walk among their corpses and confront the humanity of people reduced to targets in a video game.

The game also includes moments where civilian characters challenge Walker directly. One notable scene has a mob of refugees attempt to lynch Lugo after discovering Delta Force destroyed Dubai’s remaining water supply. Players can choose to shoot the civilians or fire warning shots, but the scene forces a confrontation with the consequences of your actions through the eyes of those affected. These moments work because they remove the comfortable distance most shooters maintain between player actions and their impact on innocent people.

The Multiplayer Nobody Talks About

Spec Ops: The Line included a multiplayer mode that almost everyone agrees was terrible. Standard team deathmatch and objective modes set in Dubai with no connection to the single-player narrative. The multiplayer was outsourced to a different studio and feels completely at odds with the game’s anti-violence message. Many consider it the most damning evidence that Spec Ops is hypocritical, criticizing military shooters while including the exact multiplayer modes it condemns.

However, some argue the multiplayer’s existence is itself a commentary on the industry’s obsession with including multiplayer in every shooter regardless of whether it fits. Publishers and focus groups demanded multiplayer because market research showed it increased sales and player retention. The development team reportedly didn’t want to include it but were forced to by 2K Games. In that context, the disconnected, generic multiplayer becomes a perfect example of how corporate demands compromise artistic vision in game development.

Whether you view the multiplayer as hypocritical or meta-commentary depends on your perspective. Either way, almost nobody played it, and it’s been delisted along with the rest of the game since 2024 due to expired licensing agreements. The single-player campaign is what matters and what continues to provoke discussion years later.

Why It’s Still Relevant In 2026

Thirteen years after release, Spec Ops: The Line remains relevant because the issues it explores haven’t gone away. Military shooters still glorify violence, still present American military intervention as heroic, and still remove moral weight from player actions. Games have gotten technically better, but narratively most AAA shooters haven’t progressed beyond the conventions Spec Ops critiqued in 2012.

Recent discussions about the game often compare it to titles like The Last of Us Part II, another game that deliberately made players uncomfortable with violence and received backlash for subverting expectations. Both games understand that if you want to meaningfully explore violence in games, you can’t just add a sad cutscene after a fun action sequence. You need to make the violence itself feel wrong, uncomfortable, and exhausting rather than exciting and rewarding.

The game’s delisting from digital storefronts in 2024 due to expired music licenses has created new urgency around preservation. Physical copies command premium prices, and the game is becoming increasingly difficult to access legally. This has sparked debates about game preservation, corporate control of art, and whether culturally significant games deserve special treatment to keep them available.

What We Should Take From It

The lesson of Spec Ops: The Line isn’t “Don’t play video games” or “You’re bad for enjoying shooters.” The lesson is that we should think critically about the media we consume and the messages it sends. Military shooters aren’t inherently evil, but we should recognize when they’re propaganda, when they glorify real-world violence, and when they remove moral consequence from actions that would be atrocities in reality.

The game also demonstrates that video games can be art, that they can explore complex themes and make meaningful statements about violence, war, and American foreign policy. Spec Ops proved games could do what films like Apocalypse Now and Platoon did, using the medium’s unique interactivity to make players complicit in ways passive viewing can’t achieve. That ambition alone makes it worth studying even when the execution is imperfect.

FAQs

Did the developers say not to play Spec Ops: The Line?

No, this is a common misconception. Lead writer Walt Williams said playtesters feeling uncomfortable continuing showed they’d struck the right emotional tone, not that players should literally stop playing. The message is about being aware of what you’re engaging with, not avoiding it entirely.

Is Spec Ops: The Line hypocritical for having multiplayer?

The multiplayer was reportedly mandated by publisher 2K Games against the development team’s wishes. Whether this makes it hypocritical or a meta-commentary on corporate interference depends on your interpretation.

Can you avoid the white phosphorus scene?

No, using white phosphorus is mandatory to progress. However, the game’s point is that Walker could have stopped pushing forward long before reaching that scene. The lack of player choice reflects how shooters remove agency while maintaining the illusion of heroic action.

Is the gameplay intentionally bad?

The gameplay is serviceable but generic, which is intentional. The familiar mechanics lull players into the comfort zone of standard shooters before subverting expectations. Some frustrating elements like checkpoint placement are designed to make violence exhausting rather than fun.

What happened to Colonel Konrad?

Konrad died by suicide weeks before Walker arrived in Dubai, unable to cope with his failures. Every interaction with Konrad throughout the game is Walker’s hallucination, his mind creating a villain to blame for his own actions.

Can you still buy Spec Ops: The Line?

The game was delisted from digital storefronts in 2024 due to expired music licenses. Physical copies are available on secondary markets but command premium prices. There’s no official way to purchase it digitally anymore.

What does the ending mean?

The multiple endings explore whether Walker accepts responsibility for his actions or remains delusional. The most disturbing ending suggests Walker’s psyche is completely broken and he now fully believes he is Konrad.

Is Spec Ops: The Line worth playing in 2026?

If you can find a copy, absolutely. Despite dated graphics and mediocre gameplay, the narrative remains one of the most ambitious and thought-provoking stories in gaming. Just understand it’s deliberately uncomfortable and exhausting to play.

Did Spec Ops influence other games?

Games like The Last of Us Part II and This War of Mine show similar influences in how they explore violence’s consequences. However, most AAA military shooters ignored its lessons and continue glorifying combat without moral weight.

Conclusion

Thirteen years later, people still don’t understand Spec Ops: The Line because understanding it requires accepting uncomfortable truths about the games we play and the violence we enjoy. It’s easier to dismiss the game as preachy or hypocritical than to engage with its actual arguments about how military shooters normalize atrocities and remove moral consequence from violence. The game doesn’t blame you for playing it, it asks you to think about what playing it means, what the genre represents, and how games use familiar mechanics to make horrific actions feel heroic. That discomfort, that unwillingness to sit with the game’s message, is precisely what Spec Ops critiques. We want our war games to be fun escapism where we’re the hero, not uncomfortable examinations of how easily good intentions become atrocities when paired with military might and American exceptionalism. Until we’re willing to engage with those themes honestly, we’ll keep misunderstanding what Spec Ops: The Line was trying to say. Maybe that’s the real tragedy, the game that condemned military shooters for not making players think critically gets dismissed by players who refuse to think critically about it.