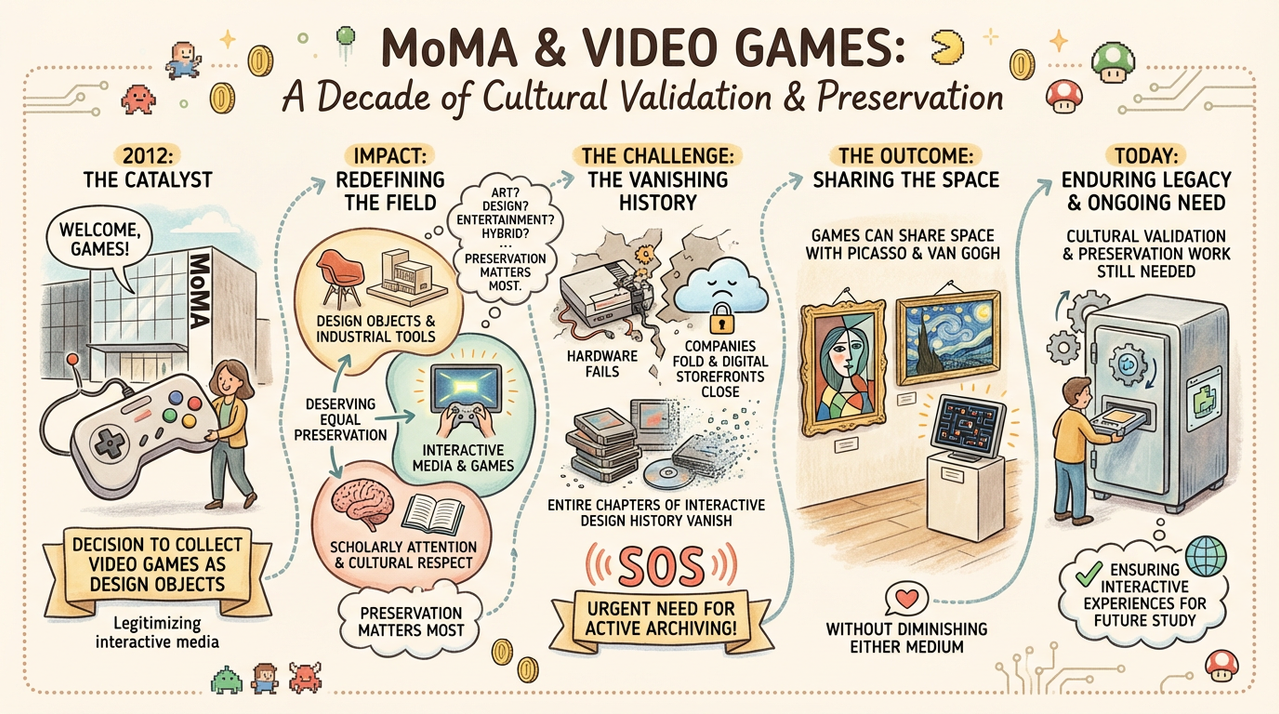

A Reddit post recently resurfaced a story that shook the art world back in 2012: the Museum of Modern Art in New York City adding video games to its permanent collection. While the news might seem fresh to some, this landmark moment happened over a decade ago when MoMA curator Paola Antonelli announced the museum would acquire 14 video games as part of its Architecture and Design collection. The decision immediately sparked heated debates about whether games deserved to stand alongside traditional fine art, and that conversation continues today.

The Original 14 Games That Made History

When MoMA unveiled its gaming collection in March 2013, the initial lineup read like a greatest hits of interactive design. Pac-Man and Tetris represented arcade classics that defined an era. Portal brought mind-bending first-person puzzle mechanics to the table. SimCity 2000 showcased complex simulation systems. The Sims demonstrated how virtual dollhouse gameplay could captivate millions.

Other selections included Another World, Dwarf Fortress, vib-ribbon, EVE Online, Passage, Canabalt, flOw, Katamari Damacy, and Myst. Each game was chosen not for nostalgia or commercial success, but for specific design innovations that pushed interactive media forward. MoMA’s approach treated games as design objects worthy of study, similar to how the museum displays everything from the original iPod to Lego blocks to Bic lighters in its permanent collection.

Why Design Instead of Art

Antonelli deliberately framed the collection through a design lens rather than directly calling games art, which was a smart strategic move. She drew parallels to Philip Johnson’s influential 1934 exhibition Machine Art, which displayed propeller blades and industrial machinery in minimalist gallery settings to highlight their functional beauty. The goal wasn’t to trigger nostalgic feelings but to create that same strange distance and shock that makes people realize how gorgeous and important design pieces actually are.

The museum’s interest focused primarily on interaction design, what curator Paul Galloway called some of the purest and clearest examples of how we engage with objects. MoMA wanted to acquire original source code whenever possible, allowing them to translate games into future technologies if original hardware became obsolete. When source code wasn’t available, they settled for simulations, emulations, cartridges, or the physical hardware itself. But the core interest remained showing the interaction by itself, stripped of marketing hype and childhood memories.

The Art Debate That Never Dies

Critics immediately questioned whether video games belonged in an art museum at all. Some argued games are commercial products designed for entertainment, not artistic expression. Others pointed out that player interaction fundamentally changes the experience in ways paintings or sculptures don’t, making traditional museum display problematic. Film critic Roger Ebert famously claimed video games could never be art, a position he softened but never fully abandoned before his death.

The counterargument emphasized that games combine multiple artistic disciplines including storytelling, animation, music, and cinematography into something greater than the sum of their parts. Many games feature original scores performed by orchestras, voice acting from accomplished actors, and visual design that rivals anything in cinema. The creative vision required to design a game world with its own internal logic and emotional resonance deserves recognition alongside other artistic mediums.

The Practical Exhibition Challenges

Actually displaying video games in a museum setting presents unique problems. Paintings are meant to hang on walls. Sculptures sit on pedestals. But games are designed for interaction in arcades or home environments, making them feel out of context in sterile gallery spaces. The average MoMA visitor spends about four seconds with each displayed item, which is nowhere near enough time to meaningfully experience even a simple game.

MoMA addressed this by presenting games in various formats. Some like Pac-Man are fully playable, placed near entrances and exits to manage foot traffic. Complex titles like SimCity 2000 appear as video demonstrations or floor-to-ceiling screenshot murals. Dwarf Fortress and EVE Online get cinematic trailer presentations highlighting their essential experiences. Games requiring significant time investment received specially developed demo versions visitors could complete during a brief museum stop.

The Collection Grows

MoMA’s original plan called for expanding to around 40 games total. By 2022, the collection had reached 36 titles displayed in the Never Alone: Video Games and Other Interactive Design exhibition. New additions included This War of Mine in 2023, NetHack in 2022, Street Fighter II in 2013, and various other classics. The museum added physical hardware too, including Ralph Baer’s Magnavox Odyssey console, the first commercial home video game system.

The wish list Antonelli published in 2012 revealed MoMA’s curatorial thinking. Spacewar, Pong, Space Invaders, Asteroids, Tempest, Yars’ Revenge, Donkey Kong, Super Mario Bros., The Legend of Zelda, Super Mario 64, Street Fighter II, Chrono Trigger, Grim Fandango, Animal Crossing, and Minecraft all eventually joined the collection. The museum leaned toward classic arcade era and 8-bit console games, reasoning that a small number of visionaries from the 1970s and 80s laid the groundwork for everything that came after.

The Never Alone Exhibition

Running from September 2022 through July 2023, Never Alone represented MoMA’s most ambitious gaming exhibition. A massive screen flashed between the 36 games in the collection, creating an atmosphere somewhere between art gallery and Times Square spectacle. Unlike traditional museum pieces meant for distant observation, Never Alone was designed for maximum accessibility and engagement, with visitors encouraged to actually play the games on display.

The exhibition explored how interactive design affects behavior, learning, and how we interact with the world. It investigated video games’ capacity to forge connections and build communities, as evidenced by crowds gathering around the Pac-Man station to cheer on players navigating ghost-filled mazes. MoMA took careful consideration of traffic flow, placing heavily played games near exits and developing shorter demo versions of time-intensive titles so visitors could experience complete gameplay arcs without camping at a single station for hours.

Why This Still Matters

MoMA’s gaming collection legitimized video games as objects worthy of preservation and scholarly study. Other institutions followed suit. The Smithsonian American Art Museum launched The Art of Video Games exhibition in 2012, showcasing 40 years of gaming evolution before touring nationally. Numerous other museums worldwide now maintain video game archives or host gaming-focused exhibitions.

The collection also highlights game preservation challenges. Many classic games only exist in proprietary formats that require increasingly rare hardware to play. Original source code gets lost when studios close or IP rights change hands. Physical media degrades over time. By actively preserving games alongside their hardware, interfaces, and original code, MoMA ensures future generations can study these design landmarks even after the technology becomes obsolete.

What’s New in 2026

While the Reddit post that sparked renewed interest references the 2012 collection launch, there is gaming-adjacent news from MoMA this year. Starting January 1, 2026, MoMA PS1 (the contemporary art institution affiliated with MoMA) became completely free for all visitors for three years as part of its 50th anniversary celebration. The change makes PS1 New York City’s largest free museum, eliminating admission barriers that often prevent broader community engagement with contemporary art.

The anniversary programming includes Greater New York, PS1’s signature exhibition gathering work from 47 artists and collectives across the NYC area, opening April 16, 2026. While not specifically gaming-focused, PS1 has historically been more experimental and boundary-pushing than its parent institution, making it a natural venue for interactive media art that blurs lines between games, installations, and social experiences.

FAQs About MoMA’s Video Game Collection

When did MoMA first add video games to its collection?

MoMA announced it was acquiring 14 video games in November 2012, with the games first displayed in the Philip Johnson Architecture and Design Galleries in March 2013. The collection has since expanded to 36 titles.

Which games are in MoMA’s permanent collection?

The original 14 included Pac-Man, Tetris, Portal, SimCity 2000, The Sims, Myst, Dwarf Fortress, EVE Online, and others. The collection now includes 36 games spanning from Pong to Minecraft, chosen for their design innovations.

Can you actually play the games at MoMA?

Some games are fully playable, like Pac-Man, while others are presented as video demonstrations, cinematic trailers, or visual displays. The presentation format depends on each game’s complexity and time investment requirements.

Why did MoMA choose games for the design collection instead of an art collection?

Curator Paola Antonelli deliberately framed games through a design lens, emphasizing interaction design and functional innovation rather than directly claiming games are art. This approach parallels how MoMA displays other design objects like the iPod and Lego blocks.

Does MoMA preserve the original game code?

When possible, MoMA acquires original source code to enable future translation if original hardware becomes obsolete. When code isn’t available, they preserve simulations, emulations, cartridges, and physical hardware.

What is the Never Alone exhibition?

Never Alone: Video Games and Other Interactive Design was a major exhibition running from September 2022 through July 2023 showcasing MoMA’s 36-game collection with emphasis on accessibility and hands-on engagement rather than passive observation.

Are video games really art?

The debate continues, but MoMA’s position is that games are definitely design, combining multiple artistic disciplines including storytelling, animation, music, and cinematography into interactive experiences worthy of preservation and study.

How does MoMA handle game preservation challenges?

The museum preserves games in multiple formats: original hardware, source code when available, emulations, and documentation. For living games like Dwarf Fortress, MoMA downloads and archives each new version as it’s released.

Conclusion

The Museum of Modern Art’s decision to collect video games may have happened over a decade ago, but its impact resonates today. By treating games as design objects worthy of preservation alongside modernist furniture, architectural models, and industrial tools, MoMA legitimized interactive media as a field deserving scholarly attention and cultural respect. Whether you believe games are art, design, entertainment, or some hybrid category that defies easy classification, the practical work of preserving these experiences for future study matters. Classic games disappear constantly as hardware fails, companies fold, and digital storefronts close. Without institutions actively archiving and maintaining these works, entire chapters of interactive design history vanish. MoMA’s collection isn’t perfect, and debates about which games deserve inclusion will rage forever. But the museum proved that video games can share space with Picasso and Van Gogh without diminishing either medium. That’s the kind of cultural validation gaming needed back in 2012, and the kind of preservation work it still desperately needs today.